Why is uniform circular motion acceleration?

October 23, 2014

A common stumbling block for new physics students is why uniform circular motion is considered acceleration. This difficulty is understandable. The concept of uniform circular motion usually comes after the student has spent some considerable time studying linear kinematics, and so acceleration has only appeared in the context of objects speeding up or slowing down. The usual answer that is given is that acceleration is a change in velocity, and velocity is a vector. Vectors have both a direction and a magnitude, so if you change either one you change the vector and have an acceleration.

I consider this answer to be unsatisfying. Of course, it’s true as far as it goes, but it seems a little arbitrary. We happened to define acceleration a particular way, but what if we had defined acceleration to be just a change in the velocity’s magnitude and dropped the direction part? Then uniform circular motion wouldn’t be acceleration! Why should we prefer the first definition?

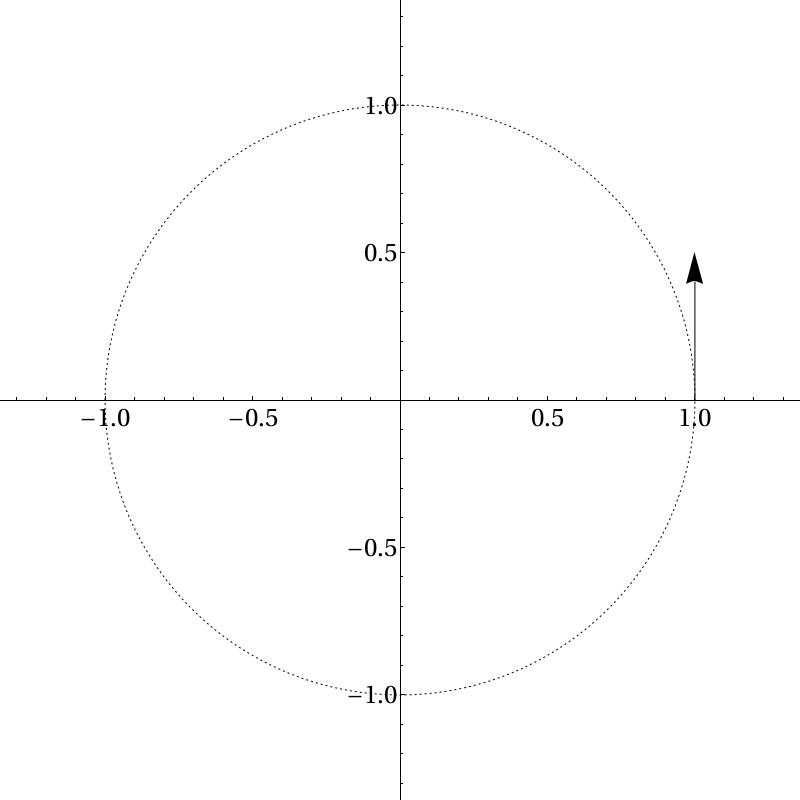

It’s easy to see that uniform circular motion feels like acceleration. If you sit in a car making a tight turn you feel yourself shoved to the side. How does this appear in the math? It helps if we lay down coordinate axes. When we start, let’s suppose we’re moving in the positive \(y\)-direction:

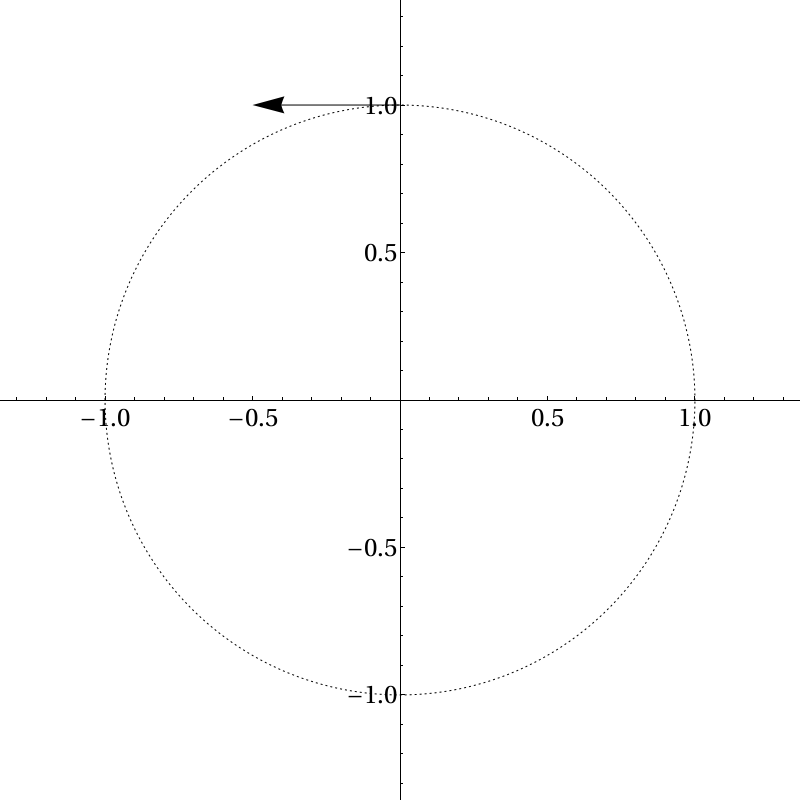

Let’s imagine we’re moving counter-clockwise, so after we’ve turned 90 degrees we will be moving in the negative \(x\)-direction, like so:

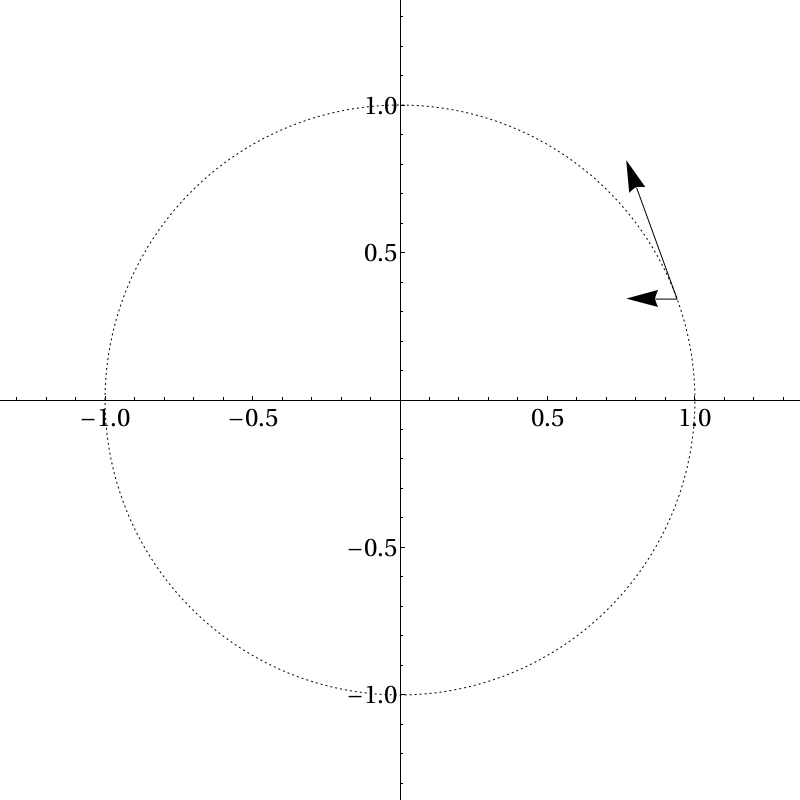

Now, a small time after we begin moving, we look like this:

Here I’ve drawn in the \(x\)-component of this vector. At this point, remember that the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates are completely independent. Anything happening in the \(x\)-direction does not care about what is happening in the \(y\)-direction and vice versa. So what is going on, then? We see that in the \(x\)-direction the object starts at rest and then starts moving in that direction, faster and faster. Likewise in the \(y\)-direction the object starts moving and then slows down to a stop. There is an acceleration in both the \(x\)- and the \(y\)-directions. If one were following along with this object, as the speed along the \(x\)-direction increases one would feel a pseudoforce in the opposite direction and as the speed along the \(y\)-direction decreases one would feel a pseudoforce along that direction. It just so happens that at all points in time if you square your speed along the \(x\)-direction and add it to the square of your speed along the \(y\)-direction, that quantity remains constant. But that has nothing to do with what your speed along the \(x\)- and \(y\)-directions individually are doing.

This seems to be a more satisfactory answer, but a clever student might raise an objection. Why did we use a Cartesian coordinate system? Isn’t that just as arbitrary as our definition of acceleration apparently was? Couldn’t we have used a polar system instead? Then the radius would remain constant and the angle would increase uniformly—once again, no acceleration!

The reason we should prefer a Cartesian coordinate system is that nature apparently does, and to explain why, we must venture into general relativity. In the absence of any matter, the Einstein field equations tell us that the geodesics of empty space are straight lines. Any observer that deviates from a geodesic will feel an acceleration. The Cartesian coordinate system works well, then, because we happened to line up our axes along geodesics! Since a circular path deviates from the geodesic, someone undergoing uniform circular motion will experience acceleration.

Do the geodesics always have to be straight lines? It turns out the answer is no. In the presence of matter geodesics can take extremely complicated shapes. If the distribution of matter is spherically symmetric then one set of geodesics consists of concentric circles centered around the center of mass. These geodesics represent objects in circular orbits around the mass. In this case, a polar coordinate system would be the preferred coordinate system to describe the physics. Since the object is following a geodesic, in the context of general relativity, it is not undergoing acceleration and an observer in such an orbit will not experience any pseudoforces.