When My Left Lung Collapsed

February 10, 2020

Sunday, February 10, 2019 began as a wonderful day. I showered in the morning and I distinctly remember feeling well rested and all around quite good. But as I was drying off I felt a sharp pain in my upper back like I had pulled a muscle or pinched a nerve.

I started to suspect that something was amiss as my wife and I walked to mass that morning. Our church is down a pretty steep hill from our apartment, so getting there is normally easy, but I was needing to walk pretty slowly. By coincidence my wife had gone to the gym for the first time after a break, so her legs were pretty sore and we both sort of hobbled to mass together. On the way back up the hill I was able to (slowly) make it back to the apartment, but I had to stop to catch my breath, which I never had to do.

Over the course of the day I found that I had trouble taking deep breaths. I was reading the Decameron at the time, so to test myself I would try reading a passage to my wife, but I usually wasn’t able to make it through an entire sentence. I didn’t really feel like moving very much, but apart from that and the fact that I couldn’t take a full breath, I felt fine. Nevertheless, that evening I made a doctor’s appointment. Fortunately there was an opening early the next morning. If you have symptoms where you’re having trouble breathing and can’t take a full breath, don’t do what I did! Go straight to the emergency room! Immediately! Like right now!

By nighttime I was starting to feel pretty crappy. It was too painful to lay on my back or my left side, so I went to sleep laying on my right side. But after a while that started to become painful, too, so I moved to the couch and slept for a while sitting up. I ended up alternating between sleeping for a bit sitting up and going back to bed to lay on my right side.

The doctor’s office

The following morning I felt completely miserable. I somehow managed to take a shower (my last for more than a week as it would turn out), but it was too painful to bend over so I had a hard time drying my legs. With some careful gymnastics I managed to put on my pants, but I couldn’t put my shoes on so I left home in my slippers instead. I booked a Lyft and took a slow, uncomfortable journey through the heavy San Francisco Monday morning traffic to the hospital.

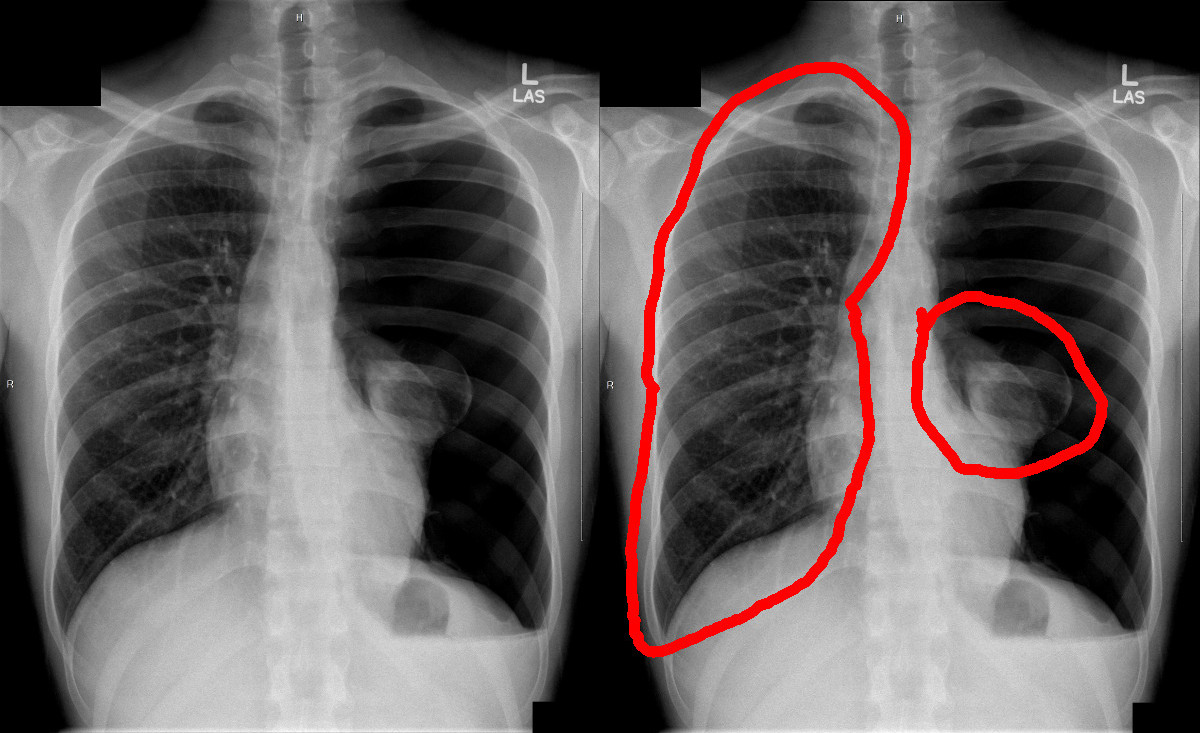

When I arrived the nurse took my vitals and then the doctor came to see me. I told her, a few words at a time, that I was having trouble taking deep breaths and had a lot of pain when I bent over or lay on my back or left side. She said, “Yes, it does sound like you’re having trouble breathing!” She listened to my lungs and said that there was definitely an issue with my left lung and there was possibly some fluid in it. She sent me to get an X-ray and told me that she was going to call the emergency doctor in the meantime.

I hobbled on over to the floor with the radiology department to get my X-ray, and after about twenty minutes or so hobbled on back to the original room. (I was actually carrying my laptop bag with me at the time because I was under some delusion, maybe born out of hopefulness that my condition wasn’t actually all that serious, that I was going to go in to work after my appointment.) After a few minutes my doctor came back and said, “So… we’re going to call 911.” She told me that my left lung had collapsed, and then a few minutes later introduced me to the emergency doctor and two SFFD paramedics who were going to take me by ambulance to the emergency room at a hospital across town. The paramedics had brought a gurney with them, but I told them I felt well enough to walk down to the ambulance (after all, I had just walked to get my X-ray!), but they told me that under no circumstances was I going to walk myself. I told them that under no circumstances was I going to lay down in the gurney because it would be incredibly painful, but fortunately they could transform it into an upright seated position and they wheeled me out into the ambulance that way.

The ambulance ride itself was fairly uneventful. I had never been in an ambulance before so I made some small talk with the paramedics in the back with me, and tried to ignore my heart rate approaching 130 bpm. Although my condition was serious, it evidently wasn’t serious enough to warrant turning on the sirens. Growing up my mother had always told me that I was lucky to have ropey veins because it would make it easier to get an IV inserted. But this was the one time my mom was mistaken because it took the paramedics about five tries before they could get the line in a vein. Maybe it’s harder to do in a moving vehicle! But the paramedics were correct in saying that I was going to become a pincushion for the foreseeable future.

So what exactly is a collapsed lung?

Before getting into more details about my experience I should go into a little more detail about what exactly a collapsed lung is. I didn’t get all this information until a few days later, but I got some of it in the emergency room so now is as good a time as any for a short primer on the condition.

The technical term for what happened to me is that I had a “spontaneous pneumothorax.” A pneumothorax is simply a medical condition where there is air in the chest cavity and outside the lung. A spontaneous pneumothorax is a pneumothorax that happens, well, spontaneously, with no obvious reason as to what caused it. By contrast a pneumothorax in general can be caused by lots of things that you would think would definitely give you a pneumothorax. Getting stabbed in the chest for instance.

Spontaneous pneumothorax cases broadly tend to fall into two groups. The first group consists of people with certain genetic disorders which predispose them to spontaneous pneumothorax. The most common of these is Marfan’s Syndrome, which manifests itself in unusually elastic tissue. This elasticity seems to predispose the lung tissue to rupture and produce a pneumothorax. The other group consists of everyone else — people who are otherwise normal and healthy, but end up with a collapsed lung anyway. Of this group, the largest demographic is thin, tall males between the ages of twenty and forty. (In my particular case, while I’m of average height at best, I do meet the other criteria.) From what I can tell it doesn’t seem to be well known what predisposes this demographic to be susceptible to spontaneous pneumothorax. One can speculate that being tall and thin tends to stretch out the lung tissue more, maybe making it thinner and more likely to rupture, but I don’t think there’s any concrete evidence to support that speculation.

So how does the spontaneous pneumothorax actually happen? The lung can sometimes have little blister-like bubbles on them called blebs. Based on autopsies, blebs seem to be somewhat common and tend to form towards the top of the lung. In rare cases (like mine), the bleb can pop, and then air leaks from the lung into the chest cavity. Once air starts to leak into the chest cavity, there’s no longer a pressure differential between the lung and the rest of the chest. This means that when the diaphragm contracts, the chest cavity will expand as normal, but this expansion will just suck air through the rupture and into the chest cavity; the lung won’t inflate (or at least it won’t inflate as much as it otherwise would). This might not necessarily be a serious problem. Sometimes a bleb can pop and there can be a partial collapse that eventually resolves itself. If the rupture is small, it can heal before too much air leaks out and the remaining air on the wrong side of the rupture can slowly permeate back into the lung over the course of several weeks.

But generally a pneumothorax is very dangerous. I was lucky because only a single lung collapsed, so I could still breathe, albeit shallowly. But if one lung completely collapses, it’s only a matter of time before it causes the other lung to collapse as well. Once both lungs collapse you can’t breathe at all and will quickly die if left untreated. Another danger is that the collapsed lung can impinge upon the heart or aorta and lead to cardiac arrest. So if you have trouble breathing, really, get treated right away!

Fortunately the immediate treatment for a pneumothorax is simple — a doctor or nurse will insert a tube into your chest, attach it to a suction pump, and pump the air out of your chest cavity. With the suction in your chest cavity, the pressure differential between the lung and the chest cavity is restored, your lung will expand when your diaphragm contracts, and you can breathe normally again. In many cases this is all that is required. If the suction is kept on for a while to ensure the lung stays expanded, the lung will often heal itself and stay inflated once the chest tube is removed (at least for a while).

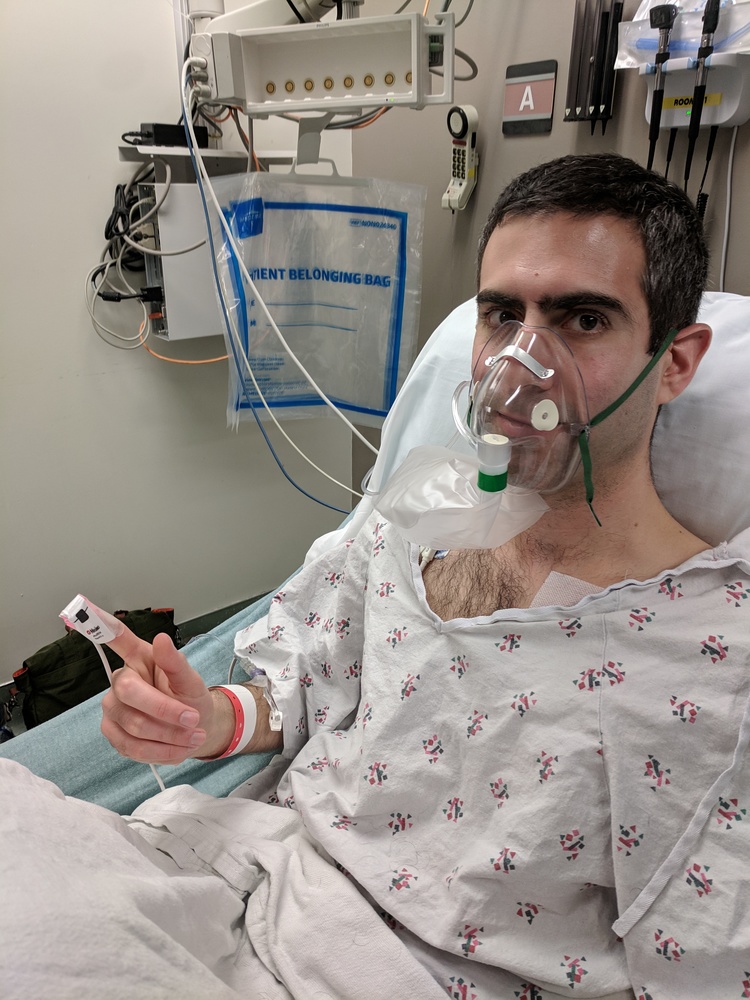

In the emergency room

The ambulance had phoned ahead to the emergency room, so as soon as I arrived at the hospital I changed into a hospital gown, was transferred to a bed (which thankfully also could be adjusted into an almost-sitting position), and was given an oxygen mask.

While I was in the ambulance I had texted my wife that I was on my way to the emergency room. She was working at Google at the time and fortunately was able to take advantage of their emergency ride program to get a ride from Mountain View to San Francisco. In the meantime she had texted my parents that I was in the emergency room and they arrived about fifteen minutes after I did, and my wife arrived about thirty minutes after that.

Not too long after my wife had arrived they started to go ahead with inserting the chest tube. One of the nurses kindly shaved the hair off the left side of my chest and then inserted the tube somewhere midway up the left side of my chest. A lot of people complain about the pain of getting a chest tube inserted, but I don’t remember feeling this one at all. That changed, however, when they turned on the suction. With the suction on, my lung started to reinflate, and it was…let’s say uncomfortable. Although the point of the chest tube is to get your lung inflated so you can breathe again, when they turned the suction I had an overwhelming sensation of being unable to breathe at all. Even when the nurses put the suction on the lowest setting, I felt like a fish pulled out of water. It was so uncomfortable (even if not exactly painful), that they stopped three times so I could catch my breath as my lung expanded.

Surgery

Once a chest tube is in and the lung is reinflated, the usual treatment for a spontaneous pneumothorax is to just wait a while to see if the lung can heal Itself. So, I was wheeled to a hospital room, and every now and again a nurse would disconnect my chest tube from suction, and then they’d wait a few hours and take a chest X-ray to see if my lung was staying up on its own. They did this for three days, but every time I was taken off suction my lung collapsed again. This was probably partly due to the fact that by the time I got treatment my lung had collapsed 100%. If I had gone to the emergency room immediately after the start of the pneumothorax the chest tube may have been enough.

In some ways the fact that my lung kept collapsing may have been a blessing, because it meant that I was eligible for a pleurodesis. While it’s nice if your lung heals itself, if you’ve had a spontaneous pneumothorax, the odds that the lung will collapse again are about 80%. A pleurodesis, however, provides a more permanent solution.

That said, the pleurodesis is not a fun surgery. As my surgeon diplomatically put it, “It is a procedure that is not without pain.” The pleurodesis is typically preceded by a “blebectomy”, where the surgeon removes the portion of the lung with the ruptured bleb (and possibly other blebs in the area). The lung is then stapled shut with a titanium surgical staple. After that the pleurodesis begins. The lung is first stripped of a thin lining of outer tissue, called the pleura. Then the lung is scarred by scrubbing it with what is essentially steel wool (this is called mechanical pleurodesis). Finally the surgeon uses a chemical to further scar the lung (this is known as chemical pleurodesis). In my case the surgeon used doxycycline as the scarring agent, although this varies. (From what I understand talc is most commonly used and is more potent than doxycycline. As I explain later this has advantages and disadvantages. Sometimes surgeons will also just do a mechanical pleurodesis or a chemical pleurodesis alone.) The steel wool and doxycycline all cause the lung to scar. The idea behind this procedure is that this scar tissue will then grow between the lung and the chest wall. This way if (or, more probably, when) another bleb ruptures, the scar tissue can keep the rest of the lung up.

In the past this procedure was a little more gruesome because the surgeon would have to pry apart two ribs to get to the lung. Thankfully these days the surgery is much less invasive; in my case I had five small incisions, three midway down my left side, one just under my armpit, and one on my back, each one about three-quarters of an inch long. The surgeon then sticks a robotic snake through these incisions to perform the surgery. (In the lingo this is called VATS — video-assisted thorascopic surgery.)

Nevertheless, thoracic surgery of any kind is no joke. The body keeps a lot of its important parts there, so while there are risks associated with any surgery, there are more risks associated with thoracic surgery than usual.

The downsides of pleurodesis

For an otherwise healthy adult, a pleurodesis is a relatively safe procedure. In the words of my surgeon, “there are no home runs, but on a scale of 1 to 10, a pleurodesis is a 1.” Given that there is a 20% chance that an individual who has had a spontaneous pneumothorax on one lung will have a spontaneous pneumothorax on the other, why don’t the doctors just perform a pleurodesis on both lungs while they’re at it?

The first reason is that although the surgery is relatively safe, it’s still extremely painful. After the surgery I wasn’t able to sleep on my left side for about three months, and I still have pain today if I sleep on that side for too long. Being able to lie down on my right side made my recovery much easier.

The other reason is that if you need to have lung surgery later in life (say, you develop lung cancer), the pleurodesis makes those future surgeries much more dangerous. The scar tissue that is keeping the lung up makes it very difficult for the surgeon to isolate the part of the lung they want to operate on and so any surgery becomes a much more delicate procedure.

A digression in support of opioids

One of the things that happens to you when you have a spontaneous pneumothorax is that you take a lot of opioids. Over the course of my recovery I became quite familiar with the different kinds and their effects: morphine, Oxycontin, Norco, Diluadid, fentanyl, Percocet. I had them all.

The surprising thing to me about the opioids was that they didn’t actually noticeably reduce my pain. I suppose the surgery was so painful that I would have had to have been drugged out of my mind to completely eliminate the pain. Nevertheless, opioids were a critical part of my recovery because even though I was still in a lot of pain, they actually doubled the volume of air I was able to breathe.

This turns out to be crucial for the recovery process. The idea of the pleurodesis is that the surgeon thoroughly aggravates the lung and then scar tissue grows between the lung and the chest wall to hold the lung up the next time a collapse happens. But in order to get the scar tissue to grow to the chest wall the lung needs to be pressed right up against the chest wall. This means that taking in deep breaths is imperative. But as you might imagine, having your lung scrubbed with steel wool and scarred with doxycycline does not exactly make it easy to breathe deep. Nevertheless, after the surgery I was instructed to do breathing exercises every six minutes.

To help you out with this, the hospital will give you a little plastic device to keep called an incentive spirometer. The incentive spirometer is a graduated cylinder with a floating disk and a tube attached. By breathing into it you can measure how much air you can inhale. I noticed that before receiving a dose of opioids, I would only be able to breathe about 750 mL of air, But after my next dose kicked in I would be breathing 1500 mL. After the does had worn off four hours later I would be back to breathing 750 mL. For context, an average adult male can breathe around 4000 mL. (I never had need to use a spirometer before my pneumothorax, so I unfortunately don’t know what my personal baseline was before my lung collapsed.)

Without opioids I would not have been able to breathe as deeply as I needed to to successfully recover from the surgery. Even still, I wouldn’t be able to breathe very deeply in the last hour before the next four hour dose. Sometimes the hospital would give me Tylenol to help tide me over between doses, but I never noticed the Tylenol making any difference.

There is another class of medications that would have been extremely effective at relieving my pain: NSAIDs like Ibuprofen, Advil, and Motrin. As the full name implies NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are good at reducing inflammation. Unfortunately that is counter-productive in this case. In a pleurodesis we want inflammation! Inflaming the tissue is the whole point so that we can grow lots of scar tissue! So NSAIDs are great at relieving the pain from a pleurodesis, but defeat the entire purpose of the operation and for that reason you’re not allowed to have them for several weeks after this surgery.

Of the opioids I was given Norco was by far the best. Percocet was not too bad, but not as effective for me as Norco was. The worst was Diluadid, which I was given once and made me nauseous to the point of vomiting.

After surgery

Going into surgery I had one tube sticking out of my chest, but when I woke up I discovered I now had two. This second tube was a little grosser than the first because it was a drainage tube. Instead of sticking out of the front of my chest, it was sticking out from my left side. It was about two feet long and had a little bulb at the end to collect blood and other fluids.

As before, the first tube was providing suction to keep my lung up while the scar tissue began to form. This tube passed through a little box with some sort of a water lock in it. Since blood would make its way through the first tube, the box would collect the excess fluid so it didn’t get sucked into the hospital’s network of pneumatic tubes. Additionally the water lock would bubble when air was being sucked out of my chest. After the surgery, the hope was that the suction box would stop bubbling because the ruptured bleb would have been removed and the hole in my lung would have been stapled up. Sadly, one day later as I was laying the hospital bed down to go to sleep I heard the bubbling start again. I didn’t realize it at the time, but it is apparently fairly common for the leak to continue a little while after the surgery since it takes a day or two for the stapled seam to heal and become airtight. Fortunately, by morning the bubbling had stopped. One of the residents took me off of suction and we waited a few hours, took an X-ray, and verified that the lung was staying up.

(Incidentally I had a lot of chest X-rays over my week in the hospital, probably somewhere around 20. I quickly learned that I have “long lungs” and a normal X-ray wouldn’t catch the bottoms of my lungs. If I forgot to tell the technician they’d have to redo the X-ray. One of the technicians joked that by the time they were done with me I would glow in the dark. Fortunately the radiation dosage from a chest X-ray is low enough that it takes on the order of 25,000 chest X-rays before you have a measurably increased chance of cancer. By comparison, it only takes 25 CAT scans.)

At this point I could be discharged from the hospital and go home. Before I could go they had to remove the chest tube that had been providing suction. One of the residents told me to take a deep breath, hunker down, and hum as loudly as I could and then he yanked it out. (This was essentially performing a Valsalva maneuver.) Once it was out I was sent on my way, although I still had the drainage tube sticking out of my side. That was to be removed a week later.

Recovery

The week that I had my drainage tube in was quite painful. I didn’t know it at the time, but the tube wraps through the chest cavity and is perhaps a foot and a half long. The tube rubs against parts of the body that normally do not have plastic tubes rubbing against them, so it creates pain, but the brain doesn’t know how to correctly interpret the pain. This produces a sensation of upper back pain in very specific spots, known as “referred pain”. During this time it was too painful to lie down so my wife and I created an enormous mound of pillows on the bed so I could sleep sitting up.

A week later I went back to the hospital to have the drainage tube removed. As with the other chest tube, I had to take a deep breath in and hunker down while the resident yanked the tube out of me. The drainage tube was longer than the original chest tube and I think some scar tissue had started to grow around it, so removing it was easily the worst pain in the entire ordeal.

Once all the tubes were out of my body I felt much better. I still couldn’t lie down, but I at least didn’t have terrible back pain anymore. My tube was removed on a Friday so I went back to work on the following Monday. I was out for a total of two weeks, one in the hospital, and one recovering at home. I was instructed not to carry anything heavier than five pounds for the six weeks after my surgery.

The recovery process was slow. It took about two months before I could sleep lying down and about five months before I could lie down on my left side. The recovery period also came with a tremendous number of strange, new sensations which I will catalog in some detail here for the benefit of anyone reading this who has recently undergone a pleurodesis and is wondering if what they’re feeling is normal.

The oddest sensation is what is called “pleural friction rub.” It was most prominent when I would lie down and it sort of felt like a tugging in my chest cavity as I breathed. Imagine the feeling of stepping on freshly fallen snow, but that feeling is inside your body as you breathe. Pleural friction rub occurs because the lung tissue is inflamed and has lost the natural lubrication that allows it slide along the chest wall. Consequently, when you breathe, the lung tissue catches as it slides along. Pleural friction rub is temporary, however, and it went away for me after about three months.

Miraculously, I think I went more than six weeks without sneezing. Had I sneezed I think my lung would have collapsed all over again! (Well, it probably wouldn’t have, but I wasn’t taking any chances!) I became really quite good at catching myself before I went into a sneeze and suppressing it. Even a very small cough felt like I was blowing out a rib. But you can’t go forever without sneezing, so for anyone who is currently recovering from a pleurodesis, a trick I learned was to tightly clutch the area with the incision before coughing or sneezing. That dramatically reduces the pain.

The recovery was also accompanied by a lot of chest pain. Pleurodesis can do a lot of nerve damage within the chest. The nerve roots will grow back to some extent, but they do so slowly and painfully, so for many months after surgery I felt throbbing pains in various parts of my chest. Numbness is also a common outcome and parts of my left side and chest are now numb, although the affected areas have slowly shrunk over time. I also frequently experience muscle spasms in my chest which I assume is also due to the nerve damage.

The final, strange sensation that I’ll document here is a sort of pressure on the side of my trachea for two weeks about six months after the surgery. It almost felt as though my trachea had been slightly displaced to one side. A tracheal deviation can actually occur during a spontaneous pneumothorax (when I first went to the doctor for my pneumothorax she checked to make sure my trachea was still centered), but once the underlying pneumothorax has been cured, the deviation should go away. (The trachea actually isn’t connected to anything in the throat but just sort of floats in place on top of the lungs.) I was also told that the intubation during surgery is pretty severe and can cause throat irritation, but that it should go away after a few weeks. So I’m still not exactly sure what caused this sensation, but other people who have experienced a spontaneous pneumothorax have told me that they have felt the same thing. I wonder if maybe there can occasionally be a small leak that shifts the lungs just enough to put a little pressure on one side of the trachea. But that is just speculation.

Gradually life has gotten more or less back to normal. Today I can easily breathe over 3000 mL on my spirometer (twice as much as I was breathing after surgery with pain medication, and four times more without), and I wrote much of this post on an airplane somewhere over the middle of Greenland, flying back to San Francisco from England. One of the more delicate questions in recovering from a spontaneous pneumothorax is when you can fly again. Even in a pressurized cabin, the air pressure during a flight is much lower than normal atmospheric pressure (perhaps 75% or so), and the change happens quickly — all recipes for a recurrence. In the past doctors were fairly conservative and recommended waiting six months to a year before flying again. But my doctor told me that these days after a pleurodesis the chance of having a recurrence during an airplane flight is minimal. I don’t think he gave me a fixed time when it would be safe, but after three months flying would likely be fine. In my case, my first flight was nine months after the pneumothorax, and I only felt a little chest tightness on the first flight (which may have been imagined).

Although flying is generally okay, scuba diving is permanently out if you have had a spontaneous pneumothorax. Scuba diving subjects the body to high enough pressures to risk rupturing another bleb. And if your lung collapses under water, Boyle’s law guarantees that surfacing is not going to make things any better.

I still have trouble sleeping for an extended period of time on my left side, and the chest numbness, pain, and spasms are still present, though reduced. In principle I should be able to do any physical activity that I could do before, with the exception of scuba diving and skydiving (too big a pressure change). I do, however, have the feeling that if I were to do a heavy deadlift I might cause another bleb to pop or rip some scar tissue, or something. But I do know that other people who have had a spontaneous pneumothorax have been able to weightlift.

So, for anyone reading this who is currently recovering from a pleurodesis, know that, despite my complaining, you will get better and life will go back to normal! Or 98% normal, anyway. And while there is still a 20% chance that this will happen all over again on my right lung, having gone through it once I think the second time will be easier now that I know what’s coming. But here’s to hoping it won’t come at all!