What is a dex?

September 25, 2014

The term “dex” comes up rather frequently in astronomy discussions but is rarely defined in textbooks. The idea of a dex is straightforward—a dex is simply an order of magnitude. More formally, a difference of \(x\) dex is a change by a factor of \(10^x\). (Although the dex is almost always used in relation to some other quantity, it can in principle be used to represent a unitless number. Thus the number \(x\) can be written \(10^x\) dex.)

We use the terms “order of magnitude” and “factor of \(x\)” all the time, though, so why use the term dex? The reason is that it comes in handy when talking about fractions of an order of magnitude. It’s particularly useful when talking about metallicity. Metallicity is measured logarithmically relative to the abundance of metals in the Sun, and accordingly it must be unitless.

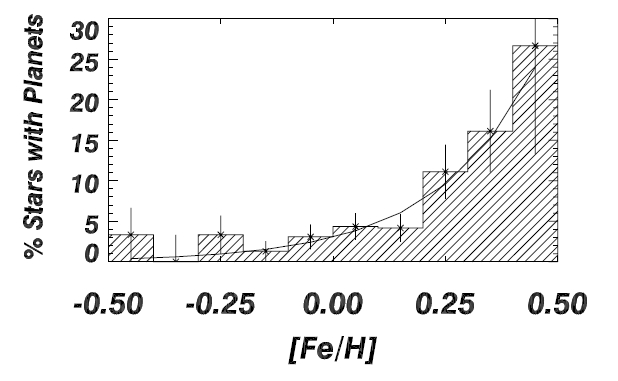

As an example, let’s take a look at Fischer & Valenti (2005). In this paper the authors present a correlation between the metallicity of stars and the probability that the star hosts a planet—stars with higher metallicities are more likely to host a planet. This result is shown in figure 5:

We can see that the sample of stars spans a range of [Fe/H] from -0.5 to 0.5, which is one order of magnitude, or one dex. Although it was just as easy to say order of magnitude as it was to say dex in that case, suppose we asked how wide the bins in this histogram were. There are ten bins spanning an order of magnitude, so the width of each bin is a factor of \(10^{0.1} \approx 1.26\). This is clumsy, so instead we simply say that each bin has a width of 0.1 dex.

A dex is completely equivalent to a “bel” or “decade” which occasionally come up in engineering and physics. The bel is much more widely known with its deci- prefix as the “decibel.” A decibel is therefore equal to 0.1 dex.

As a historical footnote, the term “dex” was coined by the astronomer C. W. Allen of Allen’s Astrophysical Quantities fame. He originally proposed the term in the 1948 meeting of the International Astronomical Union in Zurich and in 1951 published a short note advocating its use. The physicist J. B. S. Haldane took up the cause of the dex in 1960 with a short note published in Nature advocating its wider use outside of astronomy and physics, particularly in biology. It seems, however, that the biologists and other scientists were not as keen on the dex because it remains limited to the jargon of astronomy.