How Fast the Days Are Getting Longer

March 30, 2023

Here in the northern hemisphere the vernal equinox just passed and the days are quickly getting longer. One of my colleagues lives in Stavanger, Norway. Our team’s semi-weekly standup is at 6:30pm his time, so I’ve been accustomed to seeing the window in his background be pitch black for the past six months. But from one meeting to the next, his window went from pitch black to bright. This led me to think about a basic astronomy question I had never given much thought to before — just how fast do the days get longer? When Spring comes and the days are getting longer, how many extra minutes of sunlight do we get from one day to the next? So I built a little interactive graph that shows how the length of the day changes as a function of latitude, along with how it changes from one day to the next:

The vertical dashed lines represent the various solstices and equinoxes. As expected, for northern latitudes the longest day is on the summer solstice and the shortest on the winter solstice. On the equinoxes the day is exactly 12 hours no matter what latitude you are at, and this is also when the length of the day is changing the fastest — unless you are very close to the Arctic circle (latitude 66.55°).

One of the more interesting features I hadn’t appreciated before is that when you get close to the Arctic circle, the length of the days is essentially a zigzag, straight up from the winter solstice all the way to the summer solstice and back down again.

The math behind it

So what calculations are going into producing these curves?

How long is the Sun up for?

The first thing we need to know is how long the Sun is up for on a particular day of the year. Spherical astronomy has a useful quantity that lets us determine this, called the hour angle. The hour angle of an object is the angle it makes with the meridian (the line across the sky going from north to south). Converting the hour angle into a unit of time (like hours) tells us how long it will be before the object crosses the meridian (“transits” in the astronomical parlance). Since we want the time from rising to setting, the length of daylight will be twice the amount of time it takes between rising and transit:

\[t_{\textrm{daylight}} = 2H \left( \frac{24 \, \textrm{hr}}{360^{\circ}} \right) = \frac{2H}{15^{\circ}} \, \textrm{hr}.\]If we can figure out what the Sun’s hour angle is when it rises, we’ll have the amount of daylight in a day. To get this, we need to know two things: the observer’s latitude, which we’ll call \(\lambda\); and the declination of the Sun, \(\delta\), which is the angle of the Sun above the celestial equator.

A diagram (from Prof. Fiona Vincent) helps to illustrate the setup:

The position of the object we’re interested in is labeled with \(X\) in this diagram, and it shows the general case where the object is at some arbitrary altitude \(a\) above the horizon. (Note that the latitude is labeled \(\phi\) in this diagram.)

We know the lengths of all three sides of the triangle and want to find the angle \(H\). To do this we can turn to the spherical law of cosines:

\[\cos (90^{\circ} - a) = \cos (90^{\circ} - \lambda) \cos (90^{\circ} - \delta) + \sin(90^{\circ} - \lambda) \sin (90^{\circ} - \delta) \cos H.\]Since we want to know the hour angle of the Sun when it’s rising, we can set the altitude, \(a\), to 0. Solving for \(H\), this becomes

\[H = \arccos (-\tan \lambda \tan \delta).\]This is the so-called “sunrise equation.”

In order to make use of this equation we now need to find the declination of the Sun. The Sun just moves along a great circle on the sky called the “ecliptic,” and to first order this motion is approximately constant. So we can model the Sun’s declination over the course of the year with a simple sinusoid:

\[\delta \simeq \epsilon \sin \left( \frac{T}{365 \, \textrm{d}} \right),\]where \(\epsilon\) is the tilt of the Earth’s rotation axis (the “obliquity of the ecliptic” in the astronomical jargon), about \(23.45^{\circ}\), and \(T\) is just the number of days since the vernal equinox.

Putting this all together, if you have a latitude and day of the year you can calculate the length of daylight by using this formula:

\[t_{\textrm{daylight}} \approx \frac{2}{15^{\circ}} \arccos \left(-\tan \lambda \tan \left(23.45^{\circ} \times \sin \frac{2 \pi T}{365 \, \textrm{d}} \right) \right) \, \textrm{hr}.\]Daylight across the globe

There are a few interesting cases to consider in this equation. First, let’s suppose we are on the equator. In that case, our latitude is zero, and the equation just reduces to \(t_{\textrm{daylight}} = 2/15^{\circ} \arccos (0) \, \textrm{hr} = 12 \, \textrm{hr}\). On the equator, every day of the year is exactly 12 hours long.

Another case to consider is what happens on the vernal equinox. Now we set \(T\) to zero and once again the argument to the arccosine disappears, and we get 12 hours. (And because \(\cos (x + \pi) = \cos x\), this also happens on the autumnal equinox.) On an equinox, the day is exactly 12 hours long, independent of latitude.

The last thing to consider is that the arccosine function is only defined if the argument is between \(-1\) and \(1\). But the argument to the function is the product of two tangents, and the tangent function is unbounded. Let’s see what happens on the summer solstice. Here the \(\sin T\) term is exactly 1. If the product \(\tan \lambda \tan 23.45^{\circ}\) exceeds 1, then the arccosine function will be undefined. This will happen when the latitude is above \(90^{\circ} - 23.45^{\circ} = 66.55^{\circ}\). This latitude defines the Arctic circle, and at this latitude and above the length of daylight on the summer solstice is undefined. This is because at these latitudes the Sun doesn’t set at this time of the year! In the extreme limit of the north pole, \(\tan 90^{\circ} = \infty\) and the length of day is undefined all year long. At the north pole, the Sun rises just once per year, on the vernal equinox, and stays up until the autumnal equinox.

The derivative of daylight

Now that we have an equation for the length of daylight, seeing how much it changes from day to day is fairly straightforward. All we have to do is take the derivative. Converting to the more useful units of minutes / day, this ends up being:

\[\frac{dt_{\textrm{daylight}}}{dT} = \frac{576 \epsilon \cos 2\pi \widetilde{T} \tan \lambda \sec^2 (\epsilon \sin 2\pi \widetilde{T})}{73\sqrt{1 - \tan^2 \lambda \tan^2 (\epsilon \sin 2\pi \widetilde{T})}} \, \frac{\textrm{min}}{\textrm{day}},\]where to make the equation a little cleaner, I’ve used \(\widetilde{T}\) to represent the fraction of the year since the vernal equinox.

Complications

To get a relatively simple functional form, I made a few approximations in the plots and equations above. What would we have to change if we wanted a more accurate calculation?

Atmospheric refraction and the solar limb

When calculating the length of day I assumed that the day began when the Sun is right on the horizon. But this isn’t quite when sunrise is in reality. First, the Sun has a finite width, about half a degree, so when its center is right on the horizon, half of the disk is above the horizon, and we would still consider it daytime. So really we want to know when the top of the Sun reaches the horizon.

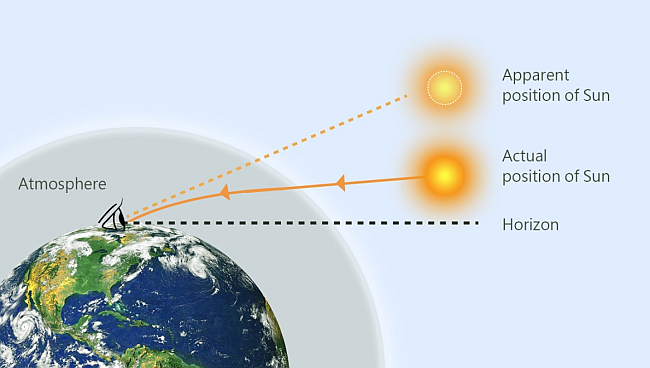

The second complication is that at the moment we observe the Sun to rise, its true position is still, in fact, beneath the horizon. But due to the refraction light by the atmosphere, the light from the Sun curves upward to make the Sun appear higher on the sky than it really is.

To take into account atmospheric refraction, we would not want to calculate the hour angle of the Sun when its altitude is zero, but when it is slightly less than zero. On the horizon, this effect turns out to be about twice as large as the width of the Sun.

Taking into account both the width of the solar disk (the “solar limb” in the jargon) and atmospheric refraction, the altitude of the Sun at sunrise or sunset is on average about \(-50^{\prime}\). (Though the atmospheric refraction varies quite a bit due to weather conditions very close to the horizon.) Unfortunately this complicates the sunrise equation quite a bit since the altitude term no longer drops out of the spherical law of cosines equation and we get

\[H = \arccos \left(-\tan \lambda \tan \delta - \frac{\sin a}{\cos \lambda \cos \delta} \right).\]You can see how much extra daylight this effect gives you at different latitudes with this plot:

A difference in altitude of \(50^{\prime}\) doesn’t sound like too much, but it adds a non-negligible amount of daylight to the day. At the latitude of Los Angeles (\(34^{\circ}\)) it adds around eight extra minutes of daylight to the day. So strictly speaking the “equinox” is a bit of a misnomer — thanks to the atmosphere the length of the day isn’t quite equal to the length of the night. Even at the equator where the effect is weakest there is 6 minutes and 40 seconds of extra daylight on the equinox, so the day is more than 13 minutes longer than the night! And at higher latitudes the impact of atmospheric refraction becomes even more pronounced. At those latitudes the ecliptic runs almost parallel to the horizon, so the Sun has to move quite a ways horizontally to make much progress in the vertical direction. For my friend in Stavanger this effect adds nearly 20 minutes to his day during the solstices. But at least until you get very close to the Arctic circle, the change in the amount of daylight from one day to the next due to this effect is relatively small.

Eccentricity and the obliquity of the ecliptic

There is a second problem with the equation I used for the length of the day. When I calculated the declination of the Sun I just modeled it as a simple sinusoid:

\[\delta \simeq \epsilon \sin \left( \frac{T}{365 \, \textrm{d}} \right).\]This is a reasonably good approximation, but it has two problems. The first is that it doesn’t properly take into account the spherical geometry. You can imagine that in the limit that the ecliptic were tilted at \(90^{\circ}\), the Sun’s declination would simply increase linearly from \(0^{\circ}\) to \(90^{\circ}\) and then back down again. Really the correct equation is

\[\delta = \arcsin \left(-\sin \epsilon \sin \left( \frac{T}{365 \, \textrm{d}} \right) \right).\]We were effectively using the small angle approximation of \(\sin x \simeq x\), along with its inverse, \(\arcsin x \simeq x\). Since \(\epsilon\), the obliquity of the ecliptic, is (sort of) small, the approximation is only off from the true value by at most \(1.5^{\circ}\), and this ends up having a fairly small impact on the change in the amount of daylight from one day to the next.

The other way that the simple model for the Sun’s declination is wrong is that it assumes that the Sun moves at a constant angular speed over the course of the year. But because the Earth’s orbit is elliptical, when the Earth is at perihelion (which occurs in early January), the Sun will appear to move somewhat faster than average and when the Earth is at aphelion (in early July), the Sun will move slower than average.

To account for the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit you’d have to turn to the Kepler equation:

\[2 \pi \widetilde{T} = E - e \sin E,\]where \(E\) is the eccentric anomaly and \(e\) is the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit. After solving this transcendental equation you’d then have to convert the eccentric anomaly into the true anomaly:

\[\nu = \arccos \left( \frac{\cos E - e}{1 - e \cos E} \right).\]This would then give you the ecliptic longitude of the true Sun rather than the ecliptic longitude of the mean Sun.

The overall impact of the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit on the length of the day is pretty minimal, however. Over the course of the year the Sun drifts from west to east with respect to the background stars. Because of this drift, the length of the solar day is about four minutes longer than the length of the sidereal day (a complete \(360^{\circ}\) rotation of the Earth). This means that near perihelion, when the Sun is moving faster than average, the day will be slightly longer than it would otherwise be. And around aphelion the day will be slightly shorter. But even at these times when the effect is maximal, the change in the length of the day is only on the order of 10 seconds (unless, as always, you’re in the Arctic circle or very close to it).

So those are few ways to find out how long the day is, some simpler and some more accurate. If you would like to see the code I used to generate the figures you can find it at this Jupyter notebook.