The discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe

February 16, 2015

Among the most important developments in cosmology was the discovery at the tail end of the twentieth century of the accelerating expansion of the universe. This result implied that around 70% of the energy density of the universe was composed of some exotic substance given the placeholder name “dark energy.” This discovery was announced in two papers that were published nearly simultaneously: Riess et al. (1998) and Perlmutter et al. (1999).

A quest for two numbers

In the three decades after the discovery of the cosmic microwave background (and with it, the verification of the big bang theory), the state of observational cosmology could accurately be called “a quest for two numbers.” Observational cosmologists worked for decades to measure two fundamental parameters that describe the expansion of the universe accurately: the Hubble constant and the deceleration parameter.

As it happens, both terms are misnomers. The Hubble constant is the rate of expansion of the universe today and has units of 1/time (i.e., it is a fractional length per unit time), but it’s usually written in the more baroque, though observationally convenient, units km/s/Mpc. The Hubble constant is an inaccurate term because it is not, in fact, constant. The Hubble constant (and many refer to it instead as the Hubble parameter) changes over cosmological timescales. If, for instance, the universe contained only matter (ignoring dark energy), then over time the expansion of the universe would slow down due to the gravitational attraction of the matter in the universe. This would mean that over time, Hubble’s “constant” would get smaller and smaller.

It is the slowing down of the expansion of the universe that the deceleration parameter is intended to measure. Of course, we now know that the expansion of the universe is speeding up rather than slowing down, so it really should have been called the “acceleration parameter,” but that wasn’t known when it was coined!

Measuring these two numbers accurately is an exceedingly difficult task and much of observational cosmology of the second half of the twentieth century was concerned with measuring these numbers reliably. The essential difficulty is that to measure these parameters one needs to measure the distance of a sample of objects at a variety of distances and their recession velocity (that is, how fast they are moving away from us). The latter measurement is not so difficult. Most astrophysical sources exhibit absorption or emission lines in their spectra. Since the rest wavelength of a spectral line is known (either from laboratory measurements or fundamental physics), the redshift of a set of spectral lines can tell us the recession velocity quite accurately.

The measurement of distances, however, is an entirely different matter. Unfortunately, celestial objects don’t come with signs on them declaring how far away they are for us! For decades, the hard problem of observational cosmology was measuring accurate distances to distant objects. To solve this problem one requires what is known as a “standard candle.” If you measure how bright it appears to be to you and you know its intrinsic luminosity, you can figure out how far away it must be.

Type Ia Supernovae

By far the most useful standard candle for cosmology has been the Type Ia supernova (SN Ia). SNe Ia are a class of supernova defined by a lack of hydrogen and helium lines in their spectra and strong silicon lines. They are among the most luminous phenomena in the universe, usually exceeding the luminosity of their host galaxy for a month or so around their peak brightness. Remarkably, all SNe Ia appear to exhibit roughly the same intrinsic luminosity. There is a dispersion of only about two magnitudes (about a factor of three in luminosity), and incredibly, this variation is very tightly correlated with the time it takes the supernova to rise to peak brightness. If the rise time of the supernova is taken into account, the intrinsic luminosity can be determined, and hence, the distance. And because SN Ia are so bright, they can be viewed across the universe, which makes them ideal cosmological tools.

So then what are these incredible type Ia supernovae? This, alas, is unknown. Due to the spectral features it is known that there is a white dwarf involved. But whether it is a white dwarf accreting matter from a main sequence star or a red giant, or merging or even colliding with another white dwarf is not known. We will discuss the evidence for all these scenarios (and a few more) in a future post.

The Evidence

The main program of SN Ia cosmology during much of the 1990s was determining the correlation between the intrinsic luminosity and the rise time. (Technically the rise time is called the “stretch factor”.) But once a reliable way to determine intrinsic luminosities of SNe Ia was established, measuring the Hubble constant and deceleration parameter was relatively easy. All that was needed was a sample of SN Ia extended out to high redshifts. Even then, the necessary sample turned out not to be very large — Riess et al. (1998) only presented ten high-redshift supernovae. But even ten supernovae were sufficient to detect the presence of dark energy to high confidence.

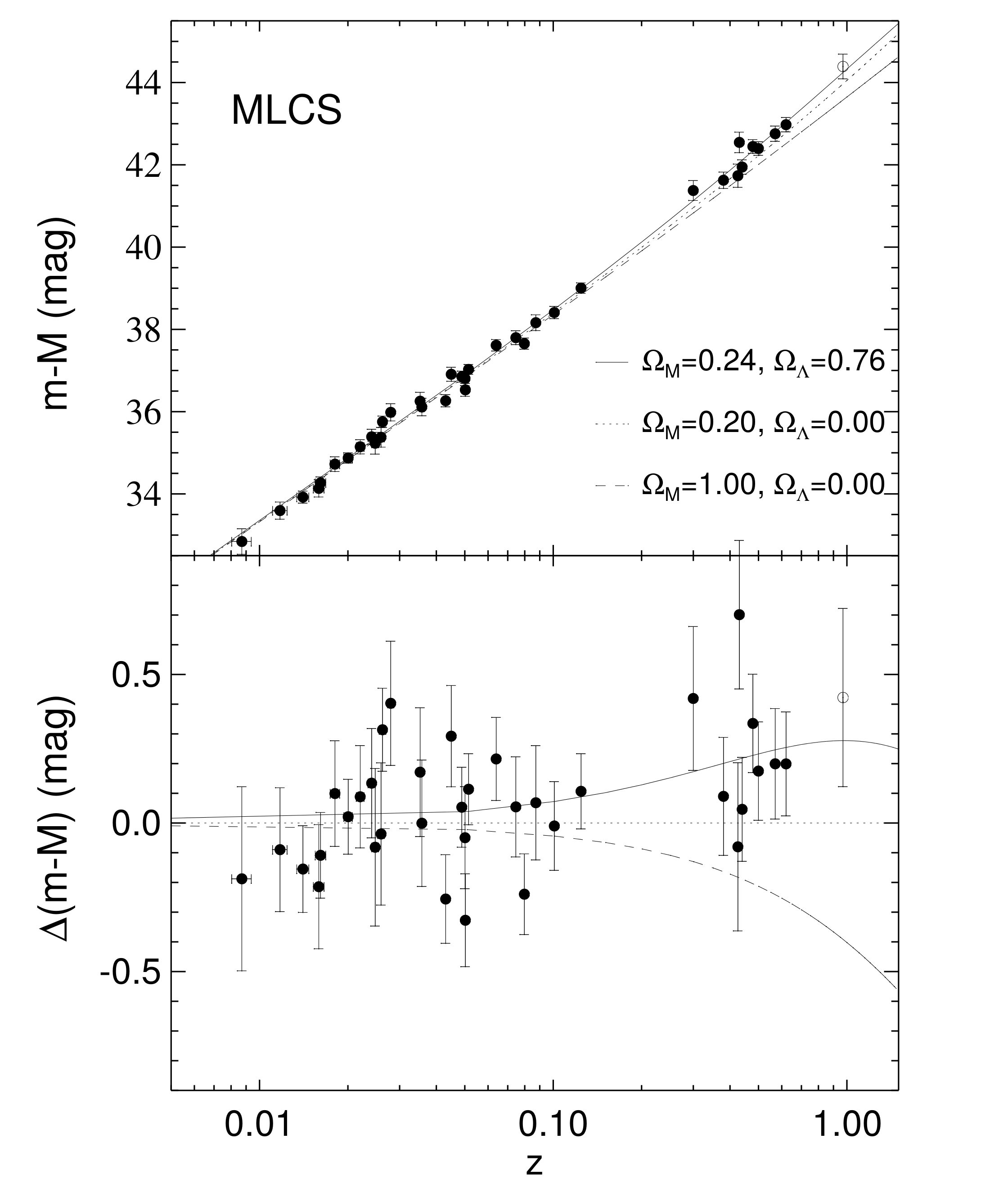

The main result of the Riess et al. paper is presented in this figure:

We have here the so-called Hubble diagram, a plot of distance vs. recessional velocity, out to redshifts of almost \(z = 0.8\). We see in the top panel how the universe would be expected to evolve in three fiducial models: one with dark energy, and two without. Of the two models without dark energy, one is a model of the universe with little matter (\(\Omega_m = 0.2\)) and the other is a model with much more matter (\(\Omega_m = 1\)). We see that the prediction for the dark energy model always lies above both of the matter-only models. This means that at any given distance (or, equivalently, at any given time in the past) a universe filled with dark energy is expanding more slowly than a matter-only universe. This can be interpreted the other way around as meaning that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. In other words, in order to get the observed present-day expansion of the universe, an accelerating universe must have been expanding more slowly in the past.

Residuals for the three models are shown in the bottom panel and it is clear that the ten high redshift supernova all lie above the two matter-only models. There is a much better fit to the dark energy model.

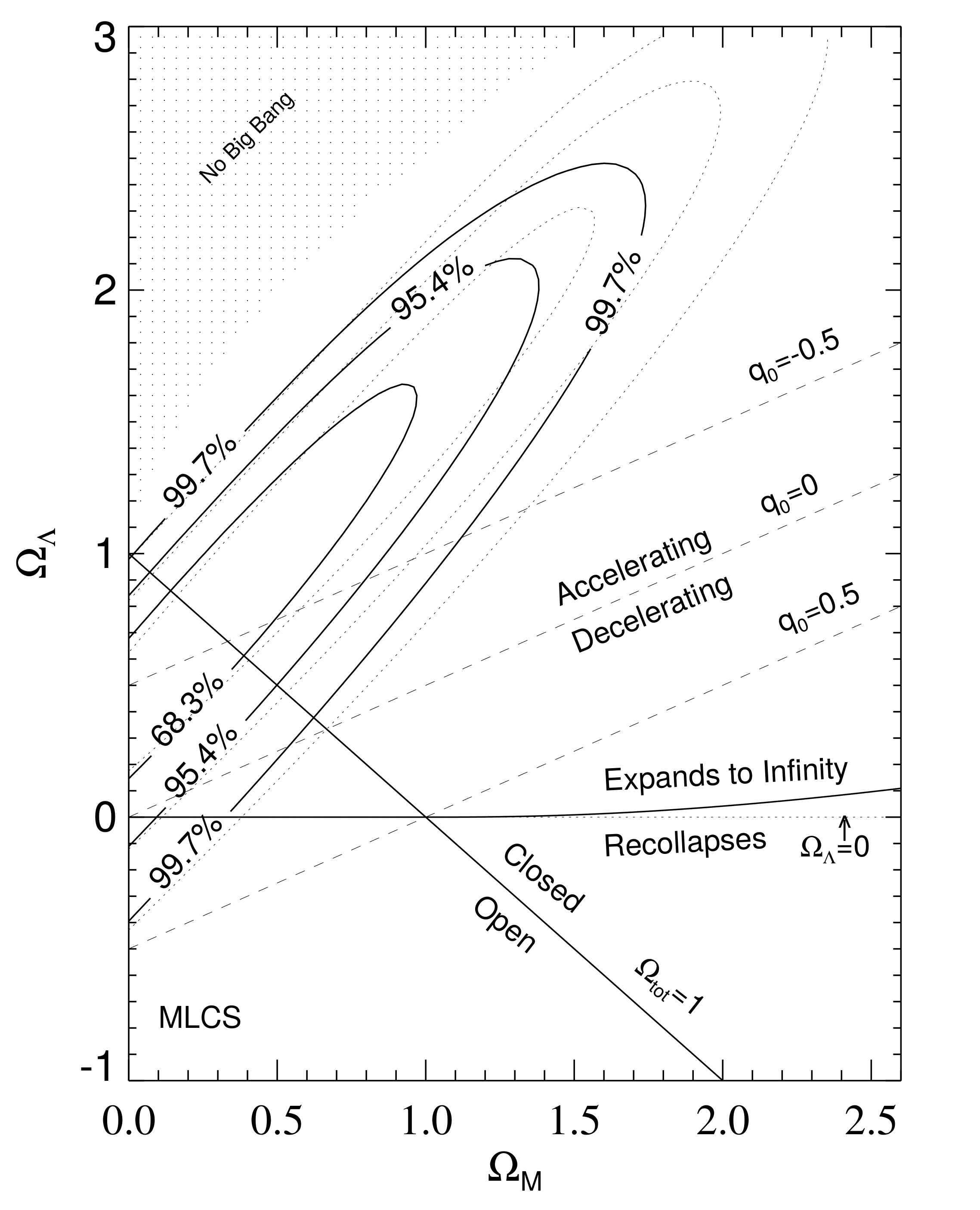

Of course, we don’t have to try just three possible models. We can try a very large number of models with all sorts of different values of \(\Omega_{\Lambda}\) and \(\Omega_m\) and see how likely it is that we would have observed the data we have. This would then tell us the relative likelihoods of all the different models:

From this figure we can see that the best fit to the data seems to be around \(\Omega_{\Lambda} = 0.7\) and \(\Omega_m = 0.3\). \(\Omega_{\Lambda} = 0\) seems to be ruled out at nearly the 95% confidence level.

The essential result is this (to quote from Riess et al.): “High-redshift SNe Ia are observed to be dimmer than expected in an empty universe (i.e., \(\Omega_m = 0\)) with no cosmological constant.”

Complications

This is an astonishing result, so it is natural to wonder if something more prosaic could be responsible for this effect. The authors of both papers consider a fairly comprehensive set of potential confounding factors that they ultimately reject.

Evolution of SNe Ia

It is possible that the SNe Ia of the early universe were somehow intrinsically different from SNe Ia today. The typical metallicities of stars in the early universe were very different from today, so it is plausible that this could have some sort of an effect on the luminosity of the SNe Ia. If these early SNe Ia were less luminous than today’s SNe Ia, this could mimic the effect of dark energy.

It turns out to be very difficult to rigorously show that SN Ia evolution is not mimicking the effect of dark energy, but the authors of both papers make a very good case that this is not likely. There have been a number studies that have looked at the effect of metallicity on SNe Ia in the local universe. These studies have not found that metallicity changes the properties of the light curve much. What seems to be more important is the age of the progenitor since younger white dwarfs evolve from more massive stars with less carbon relative to oxygen in their cores. This ultimately leads to a brighter supernova that should dim more quickly than predicted. However, there is such a large range of progenitor ages in the nearby sample that a small change in the average progenitor age from the local universe to the high-redshift universe is unlikely to bias the result much.

If high-redshift SNe Ia were intrinsically different from local SNe Ia, it is plausible that these differences would also show up in the shape of the light curve. However, there is no statistically significant difference in the distributions of the light curve shapes between the local and high-redshift SNe Ia. Of course, there are only ten SNe Ia in the high-redshift sample in the Riess et al. paper, so it is hard to make any strong statements with such a small sample, but the similarity between the two distributions is encouraging.

Lastly, one might expect that if high-redshift SNe Ia were intrinsically different from local SNe Ia, this would manifest itself in their spectra. But after comparing the spectra of the high-redshift SNe Ia to local SNe Ia the authors don’t see any obvious differences. Taken together, these results seem to imply that high-redshift SNe Ia are not extremely different from local SNe Ia.

Extinction

Distant supernovae will appear fainter than they actually are because intervening dust will absorb some of the light. This dust does not absorb light at all wavelengths equally, however; blue light is preferentially absorbed, so dust will redden the light in a characteristic way. By measuring the amount of reddening it is possible to correct for the amount of extinction.

But it is possible that dust in the early universe was different than dust in the universe today. If the dust grains were very large (bricks), they would absorb the light at all wavelengths equally. This would leave no reddening signal and we would be unable to correct for the extinction. But dust is in general patchy, so if the observed luminosities of high-redshift SNe were due to dust this would introduce a much larger dispersion than is observed. Furthermore, the high redshift universe contained a much larger amount of hard radiation which made it less hospitable for the survival of dust grains.

Selection bias

The bane of observational astronomers is, of course, selection bias. Brighter objects can be seen out to larger distances, so any sample that probes to the faintest detectable sources will have a disproportionate number of intrinsically bright members. But this turns out not to be one of the few measurements in astronomy that does not suffer much from selection bias. Although the distant SNe Ia will be intrinsically brighter, this is accounted for in the longer rise time of the SNe.

The possibility of a local void

If the Milky Way happened to be in a region of space which is relatively underdense compared to the rest of the universe, the gravitational force slowing the expansion of the universe won’t be as strong. This means that local galaxies will be receding from us more quickly than they otherwise would have without the presence of the void. Then, relative to these local galaxies, more distant galaxies will appear to be receding more slowly than they should be. This effect will then mimic the effect of dark energy.

There is, in fact, some evidence that the Milky Way resides in a local void out to about 100 Mpc. It is straightforward enough to see if the accelerating expansion of the universe is due to a void — just throw out all the supernovae within 100 Mpc and measure the cosmological parameters again. When this is done, there is no real difference (aside from a reduction in the confidence of the results).

Weak gravitational lensing

Gravitational lensing is a well known effect where the presence of mass acts as a lens, gravitationally bending light from a background source around itself and focusing it for the observer. But if the intensity is increased in one direction, it must be decreased in some other direction. And, in fact, there are many more directions along which the intensity is decreased than there are directions in which the intensity is increased. This means that if you view the source from some random direction, it is more likely that the intensity will be decreased slightly.

It is therefore possible that the light from the distant supernovae in the sample was been gravitationally defocused, making them appear fainter than they really are and mimicking the dark energy signal. Given the amount of matter in the universe, however, it is possible to calculate the magnitude of this effet and it turns out to be negligible.

Sample contamination

Type Ia supernovae are brighter than core collapse supernovae by about two magnitudes on average (a factor of six or so). This means that if some of the supposed SNe Ia in the high-redshift sample were actually core collapse supernovae, they would be dimmer than expected, thereby mimicking the signal from dark energy.

The only way to properly address this possibility is through spectroscopy. With a spectrum it is possible to unambiguously classify the supernova as a SN Ia or a core collapse supernova. Unfortunately spectroscopy of such distant objects is difficult, so three of the high redshift SNe Ia in the Riess et al. paper had poor spectra. It is possible (though unlikely) that these three were actually Type Ic supernovae and biased the measurement of the cosmological parameters to a non-zero cosmological constant. This problem can be addressed by throwing out the supernovae with poor spectra and measuring the cosmological parameters again. When this is done the non-zero cosmological constant remains.

The result

These measurements demonstrated to high confidence that the expansion of the universe is accelerating and that the majority of the energy density of the universe consists of dark energy. This was a truly revolutionary discovery. With it, cosmology completed its quest for two numbers and entered into the age of “precision cosmology.” Now that the existence of dark energy is known, the problem of modern-day cosmology has become understanding what it is. This open question will be the subject of a future post.